Slave Stories of Cass County

Video: Tom Rafiner talks about the illustration of Mastin Gant and his forage team.

Rafiner talks about illustrations in his book, “Caught Between Three Fires: Cass County, MO., Chaos & Order No. 11 1860 – 1865.” Illustrator Brian Hawkins lives in Harrisonville, Cass County, MO

Maria Rodgers Martin

1831 – 1922

Abducted from Wayside Rest in 1862, served as Senator Jim Lane’s household servant. Returned to Cass County in 1900 and buried in Brown family cemetery.

Robert Allison Brown (b. Feb. 8, 1808) and his wife, Mary Jane Roddye Gillenwaters Brown (b. Dec. 30, 1819) left Tennessee with Mary Jane’s family September 10, 1842, traveling by river steamer to Lexington, Missouri. Early abstracts indicate Mrs. Brown’s parents, the Gillenwaters, had, in 1840, been granted a 40-acre land grant, the initial Missouri family holding, northwest of Harrisonville. Later documents (Wayside Rest, a narrative by R. A. Brown III, 1966) describe the family’s landing on the Missouri River banks in Lexington, riding horseback over “considerable” parts of western Missouri, locating the land in Van Buren (now Cass) County, and then moving the family to Harrisonville, October 20, 1842.

Brown purchased over 2,000 acres including a stream which powered a steam saw built by R. A. Brown, and he opened the first grist mill in the county in 1847, providing lumber, flour, meal and feed. Lumber from the mill was later used to build the homestead, Wayside Rest in 1850. Visitors often believed upon arriving at the site of the farm that they had arrived at a village.

Family members have been at home in this fine house built on the property acquired in 1843 since that time. The farming operation included hemp and row crops, cattle, sheep and horses which necessitated the construction of a spring house, well house, ice house, wood shed, cart shed, workshop, apple house, grainery, bath house and various barns. Additionally, housing for approximately fifty slaves and farm laborers was constructed around the main house and scattered throughout the property.

One of the slaves who came with the Browns from Tennessee was Maria Jane Rodgers. Family lore tells that she was a seamstress and could possibly have quilted the two pre-Civil War quilts still housed at Wayside Rest, the Feathered Star and Mississippi Oakleaf quilts. Maria married Fred Martin at Wayside Rest, and they had eight children.

One of the slaves who came with the Browns from Tennessee was Maria Jane Rodgers. Family lore tells that she was a seamstress and could possibly have quilted the two pre-Civil War quilts still housed at Wayside Rest, the Feathered Star and Mississippi Oakleaf quilts. Maria married Fred Martin at Wayside Rest, and they had eight children.

A slave, according to family lore, possibly stitched this Feathered Star pattern quilt before the Civil War. If it was Maria, she worked as a nurse in the household.

A slave, according to family lore, possibly stitched this Feathered Star pattern quilt before the Civil War. If it was Maria, she worked as a nurse in the household.

The quilt is a stunning example of fine workmanship and quality. The maker understood both quilt construction and artistry. Today the Feathered Star is considered an advanced pattern and is shown here done with flawless execution. The points are perfect, the quilt is flat and square and the quilting is done with such attention to detail, we would call it microstippling today. The alternate blocks are quilted with extensive trapunto (stuffed) quilting . It was created all by hand.

-Stories in Stitches by Dick, Bohl, Hammontree, and Britz. 2012, Kansas City Star Books.

Another quilt purported to be made by a slave is this pre-Civil War Mississippi Oak Leaf pattern. Its expert workmanship is still visible despite damage and holes. It is of cotton in red, white and blue and hand appliqués and hand quilted in the alternate blocks with a detailed basket pattern. It is bound on three sides with fringe.

Another quilt purported to be made by a slave is this pre-Civil War Mississippi Oak Leaf pattern. Its expert workmanship is still visible despite damage and holes. It is of cotton in red, white and blue and hand appliqués and hand quilted in the alternate blocks with a detailed basket pattern. It is bound on three sides with fringe.

Family history documents that Maria was taken from the Brown home in 1862 by Federal troops during one of their numerous raids on the home during the Civil War. She served Senator James Lane as his personal servant in Lawrence, Kansas. One of the children she took with her was son Benjamin P. Martin who as only three at the time. He returned to Harrisonville in 1869 and became an accomplished blacksmith.

Maria returned to Harrisonville in 1900 to live with her son Ben. She was buried in the Brown family cemetery upon her death in 1922 at the age of 91, having outlived all her children.

Dr. Joseph & Lucinda Cusick came to Missouri from Tennessee. They arrived in Cass County after 1840 and owned a farm along the western edge of the county, On Oct. 29, 1844, Cusick emancipated, in the county circuit court, a “Negro woman named Juda from slavery and involuntary servitude.” In 1858, Cusick moved to Franklin County, Kansas where he died between 1865 and 1870.

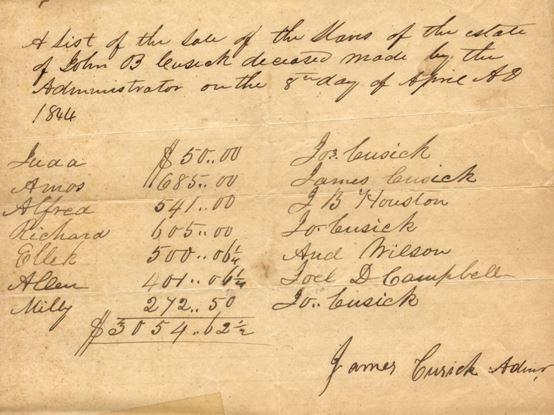

In a probate in Cass County MO Historical Society archives till box #24: John B Cusick, the first item is extensive inventory of 7 slaves. The administrator is his son James Cusick, who filed the inventory April 2, 1842.

The original appraisal of the 7 slaves provides their value. Compared with the other inventory items of which the highest value was a wagon for $150, a bay mare for $75, sorrel horses for $40 and $45, bull at $15.50, etc. for a total of $691.81, and adding up the value of the slaves at $2,550 it shows how the system was so entrenched because owners had by far the bulk of their wealth in the slaves.

Another item shows how seven negroes were hired out for the year 1842 belonging to the estate of John B. Cusick deceased:

$327.00 for 1843: $296.00 for 1844: $104.875 Total $707.875

A receipt paid by the estate to Hiram Harris for “crying” the sale July 24 1843 $2.00 and to Samuel Sharp “for crying of Negroes: Jan. 2, 1844 $.50.

A receipt filed August 19th, 1845 for $128.57

Estate of John B. Cusick to James Cusick, Admin of said estate To three percent on the amt of the sale of slaves $3,054.62.

To three percent on the amt of the hire of slaves $727.87 Interest on same $46.72

The final settlement also indicates they were trying to grow cotton as they had 11 1/2 pounds in inventory and cotton seed.

Regulating Slavery in the State of Missouri

Missouri statehood became a national controversy as Congress debated the future status of slavery in the land acquired through the Louisiana Purchase. The “Missouri Compromise” allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state, thus keeping the balance of slave and free states equal in Congress. Although Missouri entered as a slave state in 1821, the Compromise outlawed slavery in the remaining portion of the Louisiana Purchase area north of the 36°30′ line, Missouri’s southern border.

With statehood came new laws regarding black persons, including an 1825 law that prohibited a “free negro or mulatto, other than a citizen of some one of the United States” to “come into or settle in this state under any pretext whatever” (Laws of the State of Missouri, 1825, p. 600). Failure to produce a certificate of citizenship meant African Americans were forced to immediately depart from the state; during the 1844-1845 legislative session, legislators added a $10 fine in addition to the forced departure. Failure to leave the state meant a jail term and ten lashes; statutes allowed up to twenty lashes after 1845. The law did not affect free blacks passing through the state, or those who gained employment on board various steamers or other water vessels traversing the state. It also did not change the status of slaves (or their children) who obtained freedom in Missouri through court actions, emancipation, etc. They were not required to leave the state after gaining their freedom.

In 1825, the General Assembly identified a black person as one who had one-fourth part or more of “negro blood” – having three white grandparents and one black grandparent made a person “black” in the eyes of Missouri law and therefore subject to the laws governing slaves or “negroes and mulattos.” That same year, the legislature also directed county courts to appoint patrols to “visit negro quarters, and other places suspected of unlawful assemblages of slaves” (Laws , 1825, p. 614). By 1845, these patrols had permission to administer up to ten lashes to slaves found “strolling about from one plantation to another, without a pass from his master, mistress, or overseer” (Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri , 1845, p. 404). The justice of the peace could direct that up to twenty lashes be administered. Slave patrols worked at least twelve hours per month, or as many hours as the court appointing it desired; members received twenty-five cents per hour. The patrols were not, however, supposed to prevent slaves from attending Sabbath worship services. Primarily, slave patrols attempted to exert control over the slave community using fear and force. Historians agree that the patrols were probably used sporadically and only at times when white citizens feared rebellion or insurrection.

Legislators tightened slave laws throughout the 1830s, primarily with an increase in monetary fines. Masters who allowed their slaves to go at large, hire their own time, or deal as a free person, were fined between $20 and $100 for each offense. Laws prohibited selling, bartering, or delivering “vinous or spirituous liquor” to a slave. Masters who allowed the commercial interaction were fined $300; slaves who sold or delivered alcohol to other slaves could receive up to twenty-five lashes.

By 1857, in the midst of increasing hostility and sectional bitterness over the western expansion of slavery, the General Assembly attempted to pass legislation requiring that all boats and water vessels be chained and locked at night. This was an obvious attempt to limit any means by which slaves might escape to freedom. Failure to comply meant stiff penalties for negligent owners. The law did not pass, although it is evidence of intensified white citizens’ fear of the slave’s rising temptation to run away and the white community’s willingness to take extreme measures to maintain control over Missouri’s African American population.

Runaway Slave Laws

The 1804 section governing the “lying out” of slaves was repealed in 1825. In its place, though, was enacted a more stringent chapter, composed of ten sections, exclusive to runaways.

The new statutes allowed any citizen to apprehend a runaway slave and deliver said slave to the justice of the peace. Any slave found more than twenty miles from home or place of employment was considered a runaway. All runaways were committed to the local jail; the sheriff advertised such confinements at the courthouse for one month – after that, the slave was sold for expenses.

During the 1840s, legislators amended the “runaway slave” section to include a reward system. Anyone who arrested a runaway slave could receive a $100 reward if the capture took place outside of Missouri borders and the slave was over the age of twenty. If the capture took place outside the state and the slave was under the age of twenty, the reward dropped to $50. A capture within Missouri’s borders, with no age limit, netted a reward of $25. Slaves taken up within the county or counties adjoining brought a reward of $5 to $10. Now, though, sheriffs were required to advertise about the confinement of slaves for three months rather than just one; no reply meant sale of the slave at public auction. Part of the proceeds paid for boarding expenses and some helped fund the state’s university.

Persons who forged a free pass for a slave to facilitate escape, or persons who abducted or enticed slaves to escape risked a five to ten year sentence in the state penitentiary. The same sentence applied to a “free negro” who broke this law. The statute instructed the governor of the state to publish the new act in two newspapers in different parts of the state for three months and then annually thereafter.

Abolitionists

In addition to placing more restrictions on slave life, the General Assembly also attempted to prevent abolitionist influence on Missouri slaves. In 1837, the General Assembly passed an act to “prohibit the publication, circulation, and promulgation of the abolition doctrines.” A conviction subjected the offending person to a maximum fine of $1000 and two years in the state penitentiary. A second offense brought twenty years in prison; and a third offense translated to a life sentence.

Although statutes prohibited abolitionist publications in the late 1830s, a decade later, the fear of abolitionist doctrine remained strong. In 1847, the General Assembly passed an act stating that “No person shall keep or teach any school for the instruction of negroes or mulattos, in reading or writing, in this State.” An uneducated black population made white citizens feel more secure against both abolitionists and slave uprisings, although it probably did little to suppress the desire for freedom. Numerous persons and organizations defied the law. In addition, meetings, religious or otherwise, conducted by other African Americans, were prohibited unless some sheriff, constable, marshal, police officer, etc., was present. Violations could receive a $500 fine, six months in jail, or both (Laws 1847, pp. 103-104).

Conclusion

What began with the Code Noir of the French and Spanish colonial period continued over a half-century after the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory and eventually carved out Missouri. The black code measures promulgated and retained by these various governments constrained the slave and free black population and theoretically created a near-total system of control. In a slave society, slaveholders considered it necessary to monitor the daily lives of their slaves, thereby subjugating an involuntary labor force, and limit the freedom of free blacks, who might otherwise agitate and create unrest and rebellion among the slaves.

(c) 2007-2018 : Missouri Office of the Secretary of State :: Missouri State Library | Missouri State Archives :: The State Historical Society of Missouri.

For more in-depth information:

- Mutti-Burke, Diane. On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small-Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865. 2010, Univ. of Georgia Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.